The Death of the 60-40 Portfolio Could Kill Your Retirement if you Don't Prepare

My thoughts on the age-old investment advice and why it may be critically relevant for middle aged and older investors nearing retirement

The so-called “60-40” portfolio is an idea that’s been around since the 1960s, and grew out of Modern Portfolio Theory, and the pioneering work of Harry Markowitz and William F. Sharpe. These were two influential economists who made significant contributions to the field of financial economics. Sharpe’s name may sound familiar - he created the Sharpe Ratio, or the idea of mathematically expressing the idea of how excess returns over a period of time is a function of risk and volatility - rather than investor acumen or skill.

Regarding 60-40, the 60 refers to equities - stocks - and the 40 refers the bonds, principally US Treasuries (as they represent classic “risk free return”) but also investment-grade corporate and municipal bonds. The idea of the 60-40 portfolio is that for an average investor - say, someone in middle age, or midway between starting their careers and retirement, for someone of average risk tolerance, this represents an optimal mix of risk and return, the ‘sweet spot,’ if you were. Moreover, as one ages and gets closer to retirement, the idea is that you increase your allocation to “safe” government and investment-grade bonds, ease out of equities, and then ride comfortably into retirement. Once you are fully retired, you’re largely out of equities and in safe, interest bearing securities. You’re home free.

Although I am an obsessive consumer of macroeconomics and finance related content, even someone casually up to speed on the ‘lastest’ in the financing world may have heard people saying that this idea is “dead,” or at least that the 60-40 portfolio is no longer ideal and needs a serious rethink.

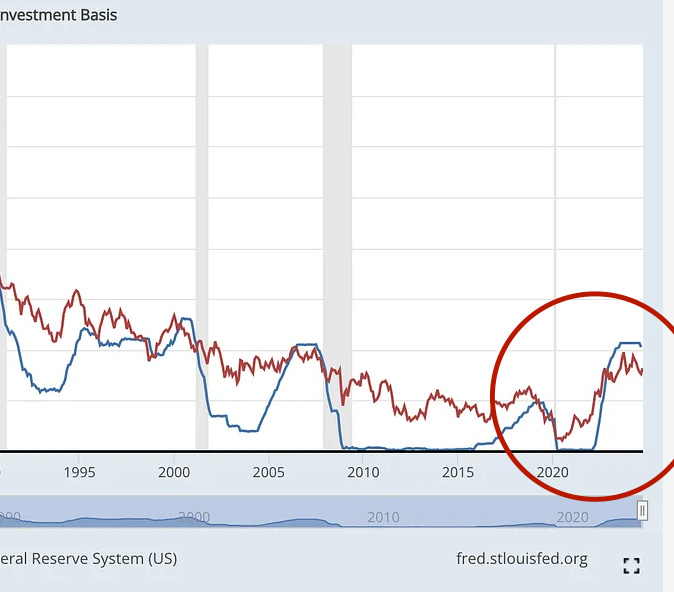

The basic idea is we are in a new regime as investors, and although there are a number of different charts to illustrate it, this is a pretty good place to start:

This is a chart of the US short term federal funds rate (also known as the “overnight rate” - which is really a range that the Fed targets more than an actual number), in blue, and the rate on the 10-year US Treasury.

Notice the peak in both charts around 1980? Yeah that was the “great inflation” of the 1970s, where in response, then Fed Chief Paul Volcker eventually jacked up the Fed funds rate to around 17.5% in order to choke off inflation, which was successful.

A few things to remember - the “price” of bonds is inverse to yields. So from the 1960s to 1980s as the blue and red lines go up, bond prices actually went down - bond prices dropped and were a terrible investment, for about 20 years. Bonds were unable to keep pace with inflation. After the 1980s, though, a series of ‘lower highs and lower lows’ were the norm, and a great bond bull market took place…. until about 2020. You can see it on the chart here:

This means that for the average, middle aged investor in their 50s (which happens to be me) - bonds, specifically those on the “long end of the curve” are no longer a good investment to buy and hold, they become relegated to simply being investment vehicles for hedge funds and traders to engage in short-term speculation.

US Treasuries and the overall Bond Market - “Certificates of Confiscation”

This is as simple an explanation as I can come up with. And yes, I think the picture above represents a trend - for around the next 15 years, give or take, bonds, particularly US Treasuries, should be regarded as “certificates of confiscation” for long term investors (a term I stole from one of my favorite online “macro finance” personalities - Luke Gromen).

There are some nuanced and somewhat complex reasons for this that depend on appreciation of monetary history - the history of debt and money. Another chart:

Although there is of course debate (as their is in so many parts of the “dismal science” of economics), it seems fairly consensus at this point that once the ratio of a country’s economic growth (e.g., GDP) measured against their fiscal debt goes consistently somewhere north of 90%, debt and currency crises (think bank failures and “liquidity panics” like 2007-2008, the 2019 “repo crisis” and the 2020 COVID panic) become more frequent and severe, and can potentially even herald a major world reserve currency shift.

As you can see although these world reserve currency shifts are a historical thing of almost clockwork regularity, it doesn’t even matter for what I’m arguing here: what is happening is the investor of the last 40-50 years, the “set it and forget it” 60-40 portfolio is no more. You cannot depend on bonds to be the safe thing in your portfolio, particularly the principal thing you lean on when you hit retirement age.

The Search for Bond-Like Proxies

Yes, I love gold (I also love silver, Bitcoin, real estate, commodities - basically any hard assets).

It’s funny - at times when I’ve advocated for the yellow metal with people on X - I get told “gold will be useless in an economic collapse, you might as well buy ammunition and canned goods!”

This is very funny, because I actually agree with them, and I don’t advocate gold because I think the USA is on the brink of a Mad Max dystopian collapse. Instead, I think that quite simply, over the next 15 years or so, the United States will have to run bond yields *below* the rate of inflation, and will do so because it has to. So that’s why I love gold - or what I’ve heard referred to as a “zero coupon bond with infinite duration.”

There is simply no runway left for the USA’s fiscal picture. We will not be able to cut spending or raise taxes to the point where we can balance the budget without sending the USA into a deflationary Great Depression. That ship sailed, likely somewhere around 2007-2008. Now we have one playbook left - devalue our currency and thereby devalue our debt burden.

But Trump will Save Us!

Unfortunately, it doesn’t matter who is in office. Whether it’s Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, the same political realities will be there, the same massive debt burden, the same fiscal realities.

The point is, prepare.

It may also be worth reading more about “Safety-First Retirement Planning” in which insurance products are used to guarantee a certain ‘safe’ level of income to meet basic expenses, one example of which is an income annuity. I’m no longer thinking about what a safe withdrawal is (4%? 1.5%?) so as not to deplete my assets before I die. Legacy is not my primary goal. Making sure we have a contractually-secure monthly or yearly income to meet basic expenses is now my focus. Disclaimer: no, I don’t sell them, I don’t own an investment firm, etc, etc.