How Will the Trump Administration Treat Older Adults?

The US's aging demographics have been repeatedly papered over by debt. These problems may likely come to a head under the Trump administration. A meditation on debt and demographics.

Think of what is happening across the industrial world, particularly places like the USA (and even more extremely - Japan, Korea, and the EU) as a sociodemographic equivalent of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object.

We’ve heard about this a million times in a million different ways at this point: around 1940, when the US Social Security system started, the so-called “dependency ratio” - or the number of workers it took to support a single retiree - was nearly 160 (although to be fair it dropped to about 16 to 1 in the 1950s).

In 2024 it’s dropped to 2.8. In about 15 years it’s projected to drop to about 2 workers. Yet for over two-thirds (67%) of boomer retirees, they depend on Social Security for a majority of their income. For about 15% of Boomers, Social Security is almost entirely their retirement income.

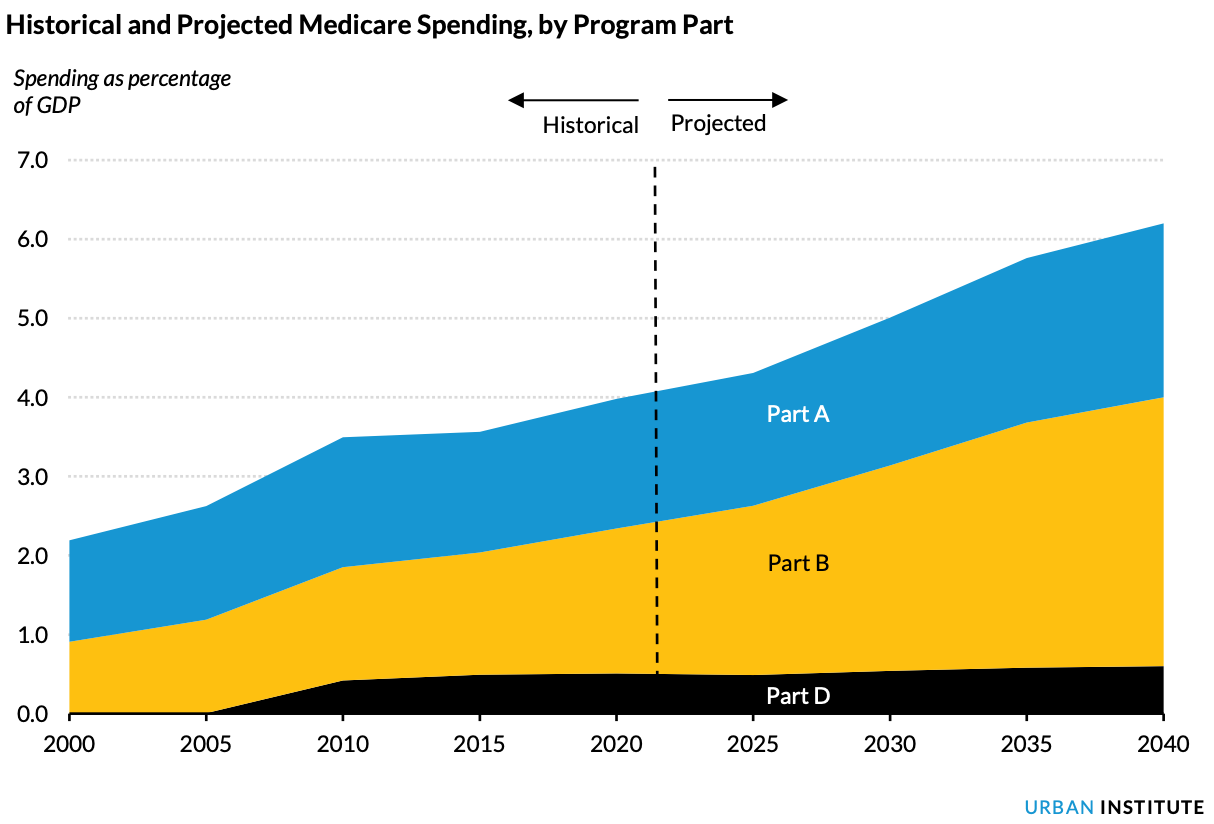

The facts are similar for Medicare, which effectively monopolizes the medical insurance market1 for older adults in the USA (and for which every working American who files a W2 with the IRS pays for): as a percentage of US Gross Domestic Product - our national income, as it were, we currently spend about 4% of our GDP on Medicare, projected to rise to 6% by 2040.

While that may not sound like a lot, we currently spend slightly less than that on the US military - approximately 3.3% of GDP on national defense (including veterans benefits). So this is a very large amount - and, the USA continues to age.

Sometime over the next 6 years (somewhere between now and 2030) we will see a full-fledged peak of Baby Boomer retirements, “peak retirement” amongst boomers. This will be the cresting of the “demographic tsunami.”

Later, sometime around the late 2040s, we will see a peak in the overall number of boomers dying. For one more visualization for you - to get a picture of what we’re dealing with as a country:

Suffice it to say, the idea here is a classic “pig through a python.” We will get through this as a country, but it’s going to be one heck of a trick to do so.

What has the US done to manage all of this so far?

You’ve probably heard this described as “kicking the can.” What is debt, anyways? It’s the idea of borrowing from future earnings to pay for today’s spending. When it’s done on productive stuff, or on a sound speculative bet—like, say, leveraging debt to purchase or expand a business, or to buy a home in a developing area—it can pay off. But that’s “good debt.”

The problem is that for the last however many decades, the United States (again, along with the rest of the Western world) has been watching its population age. As the population ages, it works less and spends more—disproportionately on healthcare, which then puts more and more stress on the tax base. Which we’ve responded to by borrowing more and more.

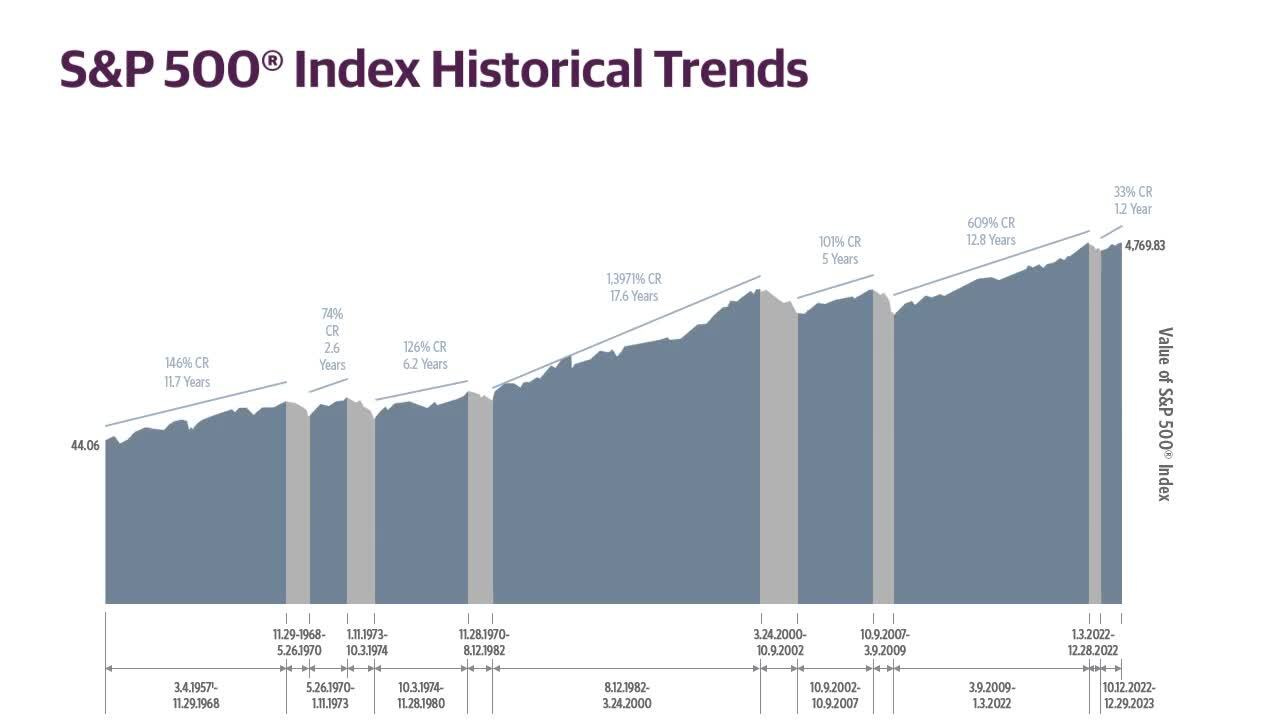

What the federal government, in concert with the Treasury and Federal Reserve, has done to address this increasing pile of debt is repeatedly inflate the monetary base—essentially monetizing debt in a way that hides most of the inflation from the general public through asset inflation - the repeated reliquification of asset classes like stocks, real estate, and precious metals markets. The charts for Bitcoin, the NASDAQ, gold, and a variety of other asset classes look similar.

I’ve talked about all of this before, but the basic idea is this - the USA is nearing a major reckoning.

What will this reckoning take the form of?

For the most part - my assumption has been that the reckoning will take the form of dollar default via inflation, or dollar devaluation. This is a view that is greatly informed by the interviews I’ve heard with this very shiny-headed midwesterner, above, Mr. Luke Gromen. To summarize what I’ve heard from him over multiple interviews, the idea is this:

Debt, particularly government debt, has become unsustainable

Government will need to bring down the debt to a point whereby the debt is sustainable via commonly understood metrics2, or a major fiscal shocks or, at best, a stagnant economy can result, both of which impart significant risks to quality of life and social stability.

There are three ways to bring down debt.

Formal default: Basically officially declaring bankruptcy, telling US Treasury debt investors they will not get paid back what they are owed. The likelihood of this happening is nil.

Default via inflation / devaluation: This is a dishonest version of default. Involves increasing the number of monetary units in circulation (“money printing,”) which can raise nominal tax revenue but makes everyone poorer in terms of their spending power. For a bunch of reasons, the burden of this form of default is overwhelmingly borne by the middle class.

Austerity: Typically understood as principally accomplished by spending cuts (as that tends to be the least economically harmful), but can also include tax raises as a way to correct fiscal imbalance.

Of the above three options, the government will likely rely disproportionately on #b, because it’s politically the easiest (I tend to agree with this).

Can Spending Cuts Help Without Hurting Older Adults?

Regarding #4 - above - Social Security, Medicare & Medicaid (along with defense and debt service payments) are considered “mandatory” spending. The idea is that as a political matter these programs cannot - and will not - be touched (at least in nominal terms), and so we need to just plan for a reality whereby they will not have their budgets cut.

I listen to a lot of macroeconomics / finance podcasts and shows.

Was watching a “Wealtheon” podcast (which is good, but not the same since the original interviewer, the super pleasant Daniel Taggart left), where PhD economist Daniel Lacalle, a widely published chief economist for the Spanish independent private bank and financial services firm, Tressis, spoke at length about the medium to long term prospects for inflation and economic growth in the coming years.

Was fascinated to hear this fellow because he was voicing something I was unfamiliar with hearing - a highly credentialed, published economist working in the field who in fact challenged what I kind of just assumed was going to be the case, above, that the United States both as a political matter and as a practical matter can’t meaningfully cut it’s spending - austerity is out of the question - and in fact the only way the USA’s fiscal imbalances (substantially caused by Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid - old age spending) are going to get addressed is through devaluation via inflation.

Yet I was surprised to hear Lacalle offering an optimistic, yet pragmatic perspective on how spending cuts can be implemented without necessarily reducing services for older adults reliant on programs like Social Security and Medicare.

According to Lacalle, much of what is categorized as "mandatory spending" in these programs includes inefficiencies and administrative costs that do not directly contribute to services. He argues that addressing these inefficiencies could yield significant savings while preserving or even improving service quality.

Lacalle explains:

“What we call mandatory spending is actually what you have to address first. But what’s important is there needs to be a process in which there’s constant education of what is being done... We’re not reducing services. We’re cutting on red tape. We’re cutting on the enormous amount of expenditure that has absolutely nothing to do with the service that is embedded in that expenditure.”

He also emphasizes that discretionary spending cuts could be achieved relatively easily by allowing temporary programs, such as those introduced under the Inflation Reduction Act, to expire. This alone could reduce federal spending by $300–350 billion annually without requiring contentious legislative battles.

Lacalle further notes:

“If they bring the deficit of 2025 from 6% or something to two [percent], then the path is much faster than what it immediately looks like.”

His argument suggests that targeted cuts in wasteful political spending and administrative overhead could reduce fiscal imbalances significantly while maintaining essential services for older adults.

What will happen to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid in the Meantime?

Well, when it comes to what’s under the purview of CMS - the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services, things will likely go on without that much changes planned in the medium or long term, and we can see this from how Trump has talked about old age programs, and from his cabinet picks.

President Trump’s cabinet nominees thus far have definitely been a mixed bag, although some have been exceptional, like Jay Bhattacharya to lead the NIH.

Some have been downright disappointing and frustrating, like Carribean medical school grad, pro-masking advocate, and frequent Fox News talking head Janet Nesheiwat as Surgeon General.

The nomination of Mehmet Oz (“Dr. Oz”) isn’t a disaster like Janet, nor a home run like Bhattacharya for NIH or Marty Makary for FDA.

Superficially, Oz is a showman, a guy who looks like his claim to fame is being a talk show host and seamy hawker of health products.

In fact, Oz is actually an accomplished surgeon with decades of medical expertise, including co-developing & patenting innovative medical technologies like the MitraClip, authoring over 400 publications, a Columbia University professorship, directorship of the Cardiovascular Institute at New York Presbyterian Medical Center, along w/ co-founding the health peer mentoring nonprofit, Healthcorps.

But running CMS is a completely different kettle of fish. In terms of the amount of money that flows through it (e.g., through the entitlement programs it manages), it’s by far one of the single biggest cabinet-level agencies in terms of its sheer economic weight (1.6 trillion dollars set to flow through it in FY2025 alone).

Dr. Oz’s experience as a physician and administrator / manager aside, it seems like his big claims to fame will be to bring his own spin on MAHA (“Make America Healthy Again”) in CMS - a focus on “holistic health” (for what that’s worth) and his love of Medicare Advantage programs, and most concerning of all, a track record of advocating for basically a form of Universal Healthcare - or so-called “Medicare Advantage For All.”

The concern I have is that Dr. Oz is, at best, simply a “business as usual” head for CMS, unlike Bhattacharya and Makary, who are clearly positioned as reformers of the bulldog variety.

Regarding Social Security - I suspect things will be even more business as usual.

What does this all mean?

This means that unless Tressis’ Daniel Lacalle’s optimistic vision of beneficial, Javier Milei-style austerity being imposed as a way of preserving Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security’s benefits isn’t realized, we still have a very bumpy road ahead. Somehow, cuts to benefits and cuts to programs, and cuts to government spending will have to happen and choices will have to be made.

The question is, do we make hard choices, or do we again kick the can down the road and let inflation make the hard choices for us?

What could possibly go wrong?

Worth noting - there’s a good argument that the third-party payer market in medical services which entities like Medicare, Blue Cross, United Health etc. occupy - which is still popularly called “insurance” - doesn’t really satisfy the traditional definition anymore. In many cases these entities aren’t functioning under the traditional insurance model of risk pooling and actuarial management, and instead are medical “prepayment plans” with aggressive cost-containment policies, often brutally and seemingly arbitrarily applied, to policyholders.

The most commonly used metric of sovereign debt sustainability is the ratio of overall debt when measured against GDP - gross domestic product (e.g., “debt to GDP.”) For reference, the US federal government’s ratio as of the end of 2024 is 123%, which greatly exceeds what is commonly understood as a critical threshold which, if exceeded, typically results in significantly higher vulnerability to fiscal shock or economic crisis. There are a number of other ways to measure debt unsustainability, however. One Luke Gromen likes to talk about is true interest expense, which includes interest on the debt plus mandatory entitlement spending, and interest payments as a percentage of revenue. Both are currently at historic highs.

Still around? I noticed the absence elsewhere.

Lots to think about there. I'd not heard the term, "pig through a python."

From the little research I did, seems apt.